The first step on this road to universal suffrage took place when parliament was dissolved on 3” December 1832 and an election was held under the reformed franchise. The Great Reform Act had made the system of the franchise for the election of MPs uniform throughout England for the first time. Some of the anomalies of the old system were addressed and the new industrial towns were enfranchised at the expense of the over-represented rural areas of England.

David Chandler

There was a steady extension of the franchise for Parliamentary elections throughout the 19th century until in 1928 we achieved the universal suffrage taken for granted today.

The Franchise up until 1832

The old franchise was limited and varied widely throughout the UK. In Wiltshire for example there were sixteen boroughs1 each returning two MPs with two returned for the county as a whole. Many “boroughs” which had been towns in the Middle Ages were now villages and were over-represented while the people in the rest of the rural county were hugely under-represented. Most boroughs were controlled by a family who had purchased the seats with a view to putting family members into Parliament where they could enrich themselves. An infamous example of this was Old Sarum where Thomas Pitt (known as ”Diamond Pitt”) purchased the property between 1691 and 1720 so he could put his son Robert into Parliament. Robert’s son became the Earl of Chatham and first sat for Old Sarum in 1734.

- A major difference with modern times is that many seats were not contested. The Wiltshire borough of Heytesbury was notorious in having no contested elections between 1689 and its extinction in 1832.

- Another difference was the high level of corruption at elections. A larger electorate meant more corruption with more electors demanding bribes. At Cricklade in the election of 1780, thousands of pounds were paid out. This came to the attention of Parliament who in an Act of 1782 threw open the election in Cricklade to all freeholders in the surrounding rural hundreds. This gave Cricklade an electorate of 1,200 (one of the largest in the country) which was now too numerous to bribe. Great Bedwyn had a larger electorate than Marlborough and elections were expensive because of the bribes demanded by voters in contested elections. An election of one member for Wootton Bassett in 1784 cost an incredible £3,000.

- Another feature of elections before 1832 was that when there was a contested election there was usually a legal challenge of the result. These petitions were heard by Parliament and were a recognised source of income for the legal profession.

- The other major difference compared to today is that a General Election was spread over a month and would be on different days throughout the kingdom. This allowed those voters with more than one vote to move around the kingdom to the different constituencies.

| In The Year | Council Men | Burgesses | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1614 | 15 | 77 | 93 |

| 1654 | 13 | 43 | 56 |

| 1704 | 9 | 31 | 40 |

| 1714 | 7 | 22 | 29 |

| 1734 | 15 | 6 | 21 |

| 1744 | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| 1745-1769 | No Records | No Records | No Records |

| 1770 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| 1780 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| 1790 | 9 | None | 8 |

| 1793 | 6 | None | 6 |

| 1800 | 8 | None | 8 |

| 1810 | 9 | None | 9 |

| 1820 | 10 | None | 10 |

| 1826 | 9 | None | 9 |

| 1830 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

This large reduction in the Burgesses shown in the table above and therefore the voters in General Elections from the reign of James Il to 1830 was mentioned in a petition to the House of Commons on 26th February 1831.

Marlborough was an example of a “Corporation Borough” where the franchise was exercised by a small number of burgesses. The number of burgesses had been 93 in the reign of James I in 1614 and had been systematically reduced to 11 by 1830. This systematic reduction had been made possible by the Charter of Queen Elizabeth in 1576 which allowed the Corporation to pass bye-laws (1717 and 1830) to restrict the franchise. The target of this reduction of the franchise was to deny dissenters and Catholics the rights of burgesses.

Marlborough had sent two MPs under this limited franchise to Parliament, since the reign of Edward I in 1300. Other “Corporation Boroughs” in Wiltshire included Caine, Wilton and Salisbury. Other types of franchise included “Burgage Boroughs” (where ownership of certain properties entitled the owners to a vote) and “Scot & Lot Boroughs” where all ratepayers had the vote. Examples of “Burgage Boroughs” were Great Bedwyn (sending two MPs up in 1832) and the notorious Old Sarum (also sending two MPs).

From the 17th Century, the borough franchises of England fell increasingly under the influence of aristocratic families: in the case of Marlborough the Bruce2 family (Tories) had succeeded the Seymour family (Whigs).

The quarrel on the Borough Council between the two parties, Whig and Tory, peaked when rival mayors were appointed from 1711 to 1714. By 1734 the Corporation was firmly in the Bruce camp and in 1771 the Corporation only agreed to nominate new burgesses with the consent of Lord Bruce. The Ailesbury’s steward was a leading member of the corporation throughout this period.

The opposition to any reform came from these ancient village “boroughs” and the families who owned them. Opposition to reform also came from larger places like Marlborough and Caine who feared they would lose their representatives.

Demands for Reform

By the late 18th century there was an increasing demand for reform. The Earl of Chatham had thoughts about reform before he died in 1778. In January 1780 a meeting of over fifty of the Wiltshire gentry in Devizes proposed a petition that recommended reform. This was addressed by no less than the radical Charles James Fox (a Wiltshire man) who expressed amazement that so many landed proprietors whose ancestors had fought for the Stuarts should now be lining up against the corruptions of the government.

However these reformist sentiments were brought to an end by the outbreak of war with revolutionary France in 1793 and didn’t resurface until over twenty years later in Reactionary sentiment had hardened during the twenty years of war with the nightmare of the Terror in Republican France.

Reform and the Marlborough Corporation

The burgesses of the borough were the electorate for parliamentary elections and there were only eleven of them in 1830. They elected a Council of nine from among their number. Burgesses were elected for life and since the mid 1700’s had been a self-selecting oligarchy. The last contested parliamentary election in Marlborough before the Great Reform Bill was in 1734 and from then until 1832, fourteen members of the Bruce and Brudenell families had been representatives in Parliament for the boroughs of Marlborough and Great Bedwyn. In the 1826 General Election a Marlborough Solicitor, John Woodman, demanded that several householders were eligible to be burgesses and put up two candidates against Lords Bruce and Brudenell. They were not successful and at the next General Election in July 1830 the campaign for reform was renewed. Several attempts were made at which John Woodman and fifteen others demanded to be admitted as burgesses. This was rejected by the Mayor and Corporation as “not being the usual mode of electing burgesses”.

John Woodman and the reformers nominated Sir Alexander Malet and John Mirehouse as candidates at the July 1830 General Election.

To the Independent Householders of Marlborough

Gentlemen,

The exercise of the Royal Prerogative in dissolving Parliament and thus calling for the true expression of the People’s wants, by enabling them to re-elect their Representatives, is to you, Alas.’ An inefficient Boon: your voices are stifled, your just influence counteracted and rendered null by the self elected Body, which still triumphing in their usurpation, pretend by sending two Anti-reformers to Parliament, to represent the opinion of the People of Marlborough. I entreat each and everyone of you to remember the obstinate perseverance of that Corporation in asserting their Monopoly, – I entreat you also never to forget that the Honourable Gentlemen who are about to be seated in the new House of Commons, as representatives of the Corporation of Marlborough, have identified themselves with the Corporate Usurpation in endeavouring to perpetuate your thraldom.

As MEN, possessed of rights of which you have been unconstitutionally deprived, – as ELECTORS, unjustly debarred the exercise of your franchise, – as ENGLISHMEN, I call upon you to remember these things: and when the day of doing Justice shall have come, as it assuredly will, I, though reluctantly compelled at present to abstain from a vain struggle in your cause, relying on your assurances and your wrongs, look forward to sharing your righteous triumph.

I have the honor to be.

Gentlemen,

Your most obedient and devoted servantAlexander Malet

London, April 26th 1831

W W Lucy. Printer,

Post Office. Marlborough

These candidates were moderates and not radicals. The reformers failed again to have their candidates elected and petitioned Parliament. They claimed in the petition that the “so called Mayor, Mr Stephen Brown, had accepted several illegal votes and rejected the good ones of the petitioners”. Such petitions were heard by a select committee of parliament and were very costly for the reformers. The reformers were obstructed by the Marlborough Corporation and the petition was heard before Sir Robert Peel in November 1830 who found for the Corporation3.

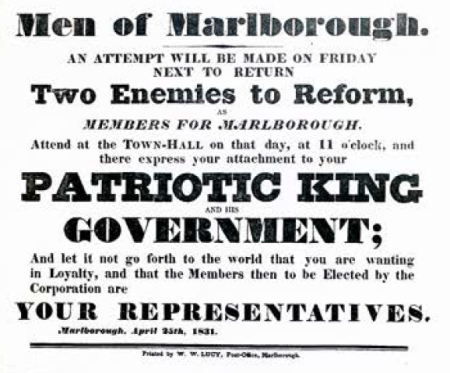

Meanwhile the Corporation struggled to get forty signatures for a petition against the Reform Bill of April 1831 while a petition in support of the Bill easily raised over four hundred signatures. Matters came to a head at the General Election of April 1831 when the reformers again nominated Sir Alexander Malet and John Mirehouse. The householders without a vote were alerted by the reformers to tum up on the day the candidates were to be elected.

The candidates nominated by the Corporation (and therefore in the Bruce interest) were Messrs Estcourt and Banks. These two Corporation candidates struggled to get a hearing and there was loud barracking during the election process. After the “Two Enemies to Reform” were pronounced elected, their effigies were paraded around the town and burnt at the crossroads. The bells of the churches were rung backwards4 in protest and the Corporation had no power to prevent this. However, the Marlborough MPs with their anti-reform and reactionary views were in a minority and it was this parliament that finally passed the “Great Reform Bill” in June 1832.

The effect of the Reform Act was to widen the franchise and make it uniform across the country. All £10 householders in boroughs (or Forty Shilling freeholders in the county) had the vote and this meant that the electorate in Marlborough went from eleven before the Act to two hundred and ninety-nine after. Marlborough retained its two seats, having had the population increased by the addition of the Parish of Preshute and its three hundred houses. This took the population above the minimum four thousand threshold for a borough to return two members. Sir Alexander Malet, the reform candidate, in a letter of December 1831 to John Woodman, joined in the celebration of the fact that Marlborough was 10 retain its two MPs.

The effect of the Reform Act was to widen the franchise and make it uniform across the country. All £10 householders in boroughs (or Forty Shilling freeholders in the county) had the vote and this meant that the electorate in Marlborough went from eleven before the Act to two hundred and ninety-nine after. Marlborough retained its two seats, having had the population increased by the addition of the Parish of Preshute and its three hundred houses. This took the population above the minimum four thousand threshold for a borough to return two members. Sir Alexander Malet, the reform candidate, in a letter of December 1831 to John Woodman, joined in the celebration of the fact that Marlborough was 10 retain its two MPs.

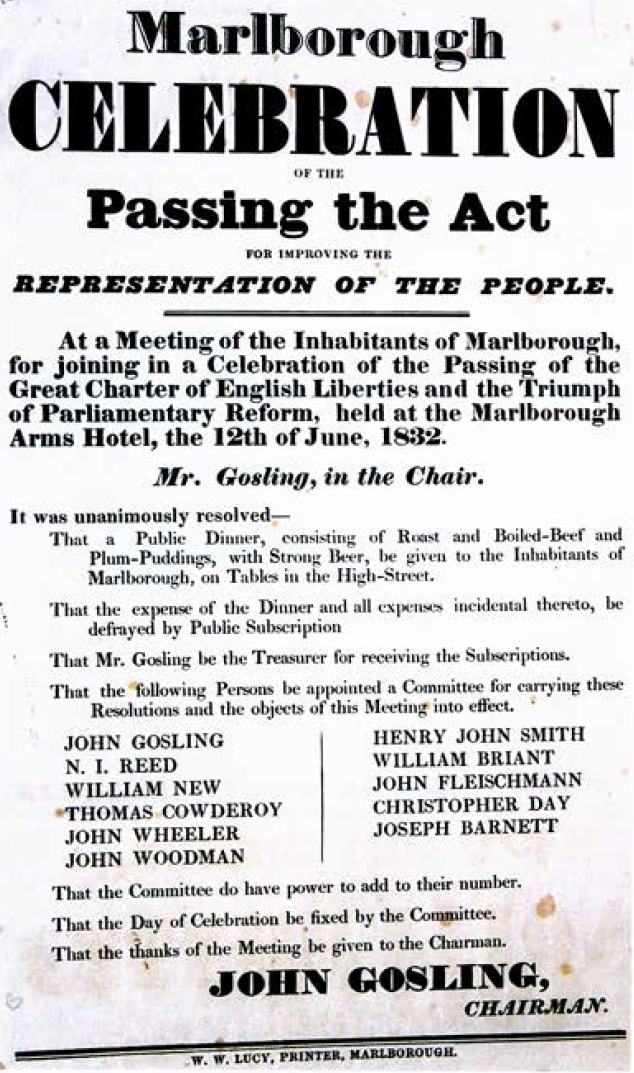

There was much rejoicing at the passing of the Act on the 12th June 1832 and the reformers proposed a celebration in Marlborough. The inhabitants of Marlborough were urged to assemble in the Green at 1:30pm on Friday 29th June and walk in procession to the High Street where tables were to be set out and a meal enjoyed by all at 2:00pm.

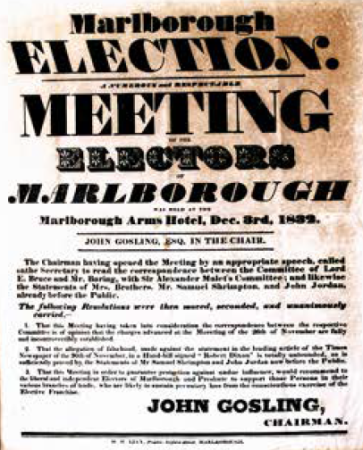

However with the prospect of a General Election later in 1832 under the reformed system there was talk of intimidation of the newly enfranchised voters. This is referred to in the poster and asks for support for those individuals who are under pressure in their businesses. The Shrimpton family who supported reform were landlords of the Castle Inn and so were tenants of the Ailesbury estate. They must have had a difficult time. The case of John Jordan, a blacksmith from Manton, who alleged intimidation was in the Times of London of 30th November 1832.

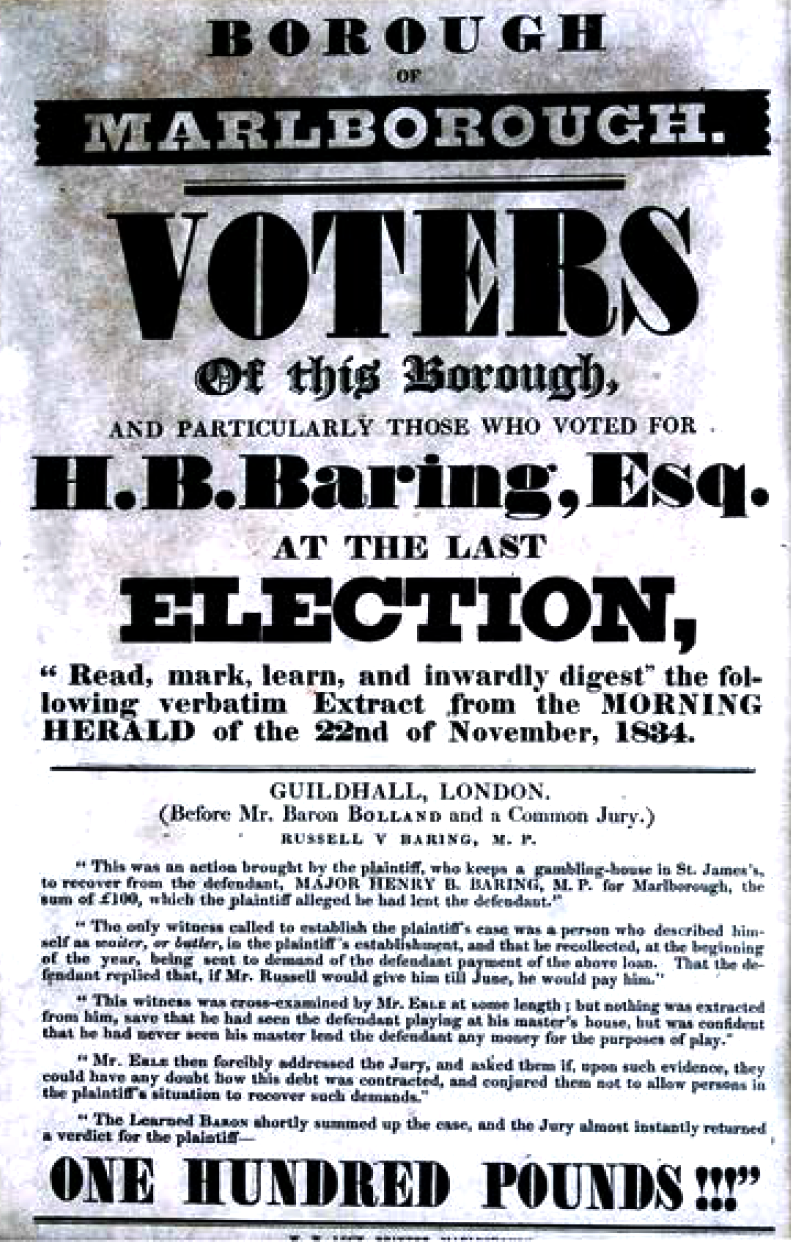

The General Election from 8th December 1832 to 8th January 1833 was the first under the new franchise. The Corporation candidates were Lord Ernest Bruce (just 21 years old) and Henry Baring while the reform candidates were Sir Alexander Malet and John Mirehouse.

There were now almost three hundred electors instead of only eleven but of the three hundred new electors over half lived in property belonging to the Ailesbury Estate.

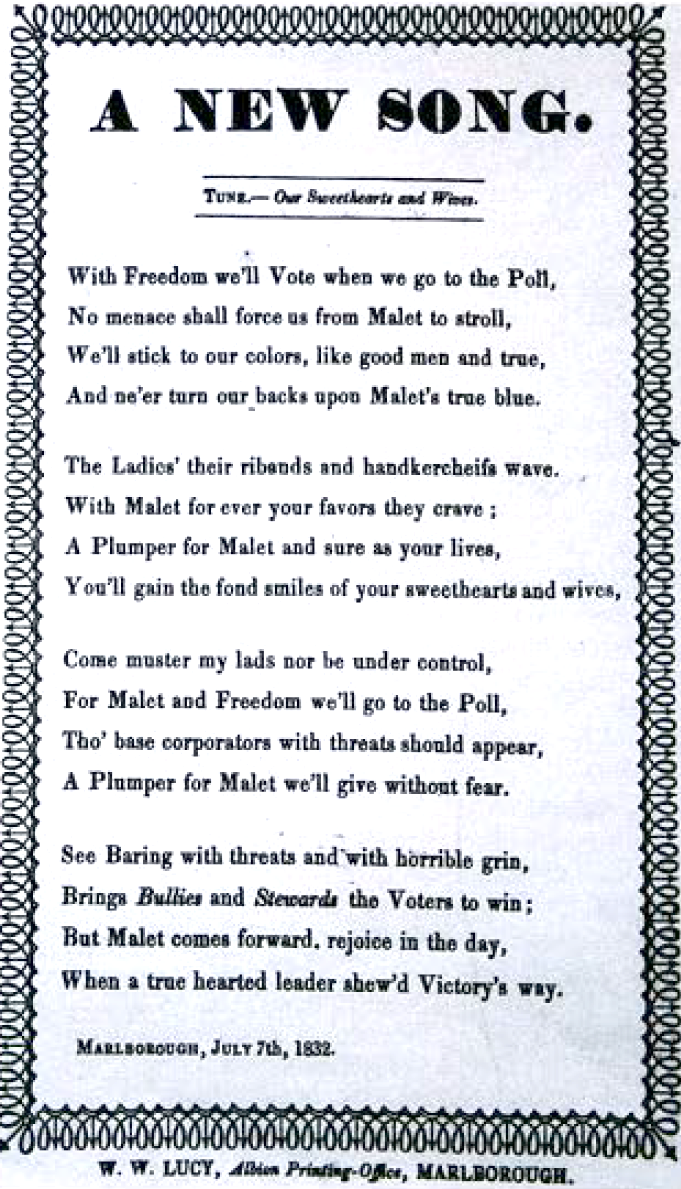

The Ailesburys were not brutal absentee landlords and were enlightened for the era. It was no surprise therefore when the Corporation nominees of Lord Ernest Bruce and Henry Baring were elected by the newly expanded franchise. However the defeat of the reform candidates at the first election under the widened franchise must have been a huge disappointment to the reformers who had fought long and hard, only to see no change in the outcome of General Elections. The atmosphere building up to the election at the end of 1832 is expressed in how the New Song fully supports Malet. The disappointment of the election result is reflected in a pamphlet of the 24′” January a few weeks after the election.

The pamphlet written by the disappointed reformers describes “A Dinner Party held by the victorious Tories which consisted not only of independent voters but his Lordship’s Corporators of Marlborough’. with some servile aspirants to that equivocal honour and other servile lovers of his Lordship’s venison”. It lampoons some of the voters at the recent election. Particular venom is reserved for members of the clergy such as the Reverend Sir Erasmus H G Williams’, the Rector of St Peter’s from 1829 10 1857. “The Reverend E H G Williams, a political waverer, who travels from Marlborough to Pembroke, from Marlborough to Carmarthen, from Marlborough to Cambridge, from Marlborough to Cricklade. 10 vote at each place for whig candidates, yet at Marlborough (upon which principle he knows best) voted for toryism and corruption.” Mr Hewitt, another voter, is described as follows” It is amusing to see Mr Hewitt, Lord Ailesbury’s former bailiff exulting in having passed from the condition of a servant, to that of a tenant. This additional length of tether gives him just room to kick up his heels. an action which he fancies will look like freedom”

The pamphlet written by the disappointed reformers describes “A Dinner Party held by the victorious Tories which consisted not only of independent voters but his Lordship’s Corporators of Marlborough’. with some servile aspirants to that equivocal honour and other servile lovers of his Lordship’s venison”. It lampoons some of the voters at the recent election. Particular venom is reserved for members of the clergy such as the Reverend Sir Erasmus H G Williams’, the Rector of St Peter’s from 1829 10 1857. “The Reverend E H G Williams, a political waverer, who travels from Marlborough to Pembroke, from Marlborough to Carmarthen, from Marlborough to Cambridge, from Marlborough to Cricklade. 10 vote at each place for whig candidates, yet at Marlborough (upon which principle he knows best) voted for toryism and corruption.” Mr Hewitt, another voter, is described as follows” It is amusing to see Mr Hewitt, Lord Ailesbury’s former bailiff exulting in having passed from the condition of a servant, to that of a tenant. This additional length of tether gives him just room to kick up his heels. an action which he fancies will look like freedom”

The pamphlet is signed by “One of the Seventy Three” 6

There was no contest in the following three General elections of 1835, 1837 & 1841 and Lord Ernest Bruce and H Baring served as the town’s MP’s until the second reform act in 1867 when the representation was reduced to one. Lord Ernest Bruce continued as the town’s one MP until 1885 (the third reform act) when Marlborough became part of the Devizes constituency. Lord Bruce by the end of his time as MP was a supporter of widening the franchise. He was also noted for not having made a single speech in his years as an MP.

The conclusion to all the agitation for reform in the early I800’s was that the representatives in parliament were from the same stable as before the 1832 Act. They now had much more legitimacy from the wider franchise but basically not much had changed. Maybe that is how many people wanted it to be!

William Wootton Lucy

W W Lucy was the publisher of many of the reformist leaflets and had his print shop behind the Merchant’s House. The building is now used by the Merchant’s House Trust as offices. W W Lucy was also the Post Master and was putting his name as the publisher of leaflets (mostly reformist) from 1830 to 1880’s. A W W Lucy was mayor in 1857 and 1867. He published a leaflet in 18827 complaining of intimidation by Mr Iveson, his Lordship’s agent. He explains in the pamphlet that as a printer he did not endorse the content of what he was printing but was just doing his job!

Footnotes:

- The The sixteen Wiltshire Boroughs were:

- Seven which survived and existed up until 1974: Marlborough , Calne, Devizes, Salisbury, Chippenham, Wilton, Malmesbury.

- Cricklade which survived after 1832 because of its wider franchise.

- Eight which were disenfranchised in 1832 and disappeared as boroughs: Great Bedwyn, Heytesbury, Old Sarum, Downton, Westbury, Ludgershall, Hindon, Wootton Bassett.

- The county returned two members. The elections were often uncontested but when they were, they tended to be expensive and controversial. In the 1818 election the unsuccessful candidate was Benett, known to Cobbett as “Gallon Loaf Benett”. To get elected in a contested county election cost about £8,000. There were thirty-four MPs from Willshire before the reform and sixteen after.

- Bruce: Earl of Ailesbury from 1776, Marquis from 1821

- The petition of 1830, heard by Sir Robert Peel is in the Wiltshire History Centre at Chippenham. Unfortunately it is very difficult to read.

- “Ringing the bells backwards”. As a bellringer I am not sure what this means. I think it might refer to something done to alert the populace in emergencies such as a fire. The significance of this is now lost!!

- The Reverend Sir Erasmus Williams became the first chaplain to Marlborough College when it was founded in 1844. He had fallen out with the College by I853 when he campaigned against a suggestion that the College and Marlborough Grammar School should amalgamate.

- I have not found any other reference to “the seventy three” and think it must refer to seventy three votes for the unsuccessful reform candidates. The numbers would be correct with the increased numbers of voters.

- I am not sure if this is the same Lucy as it is now fifty years after the Reform Act. I am also not sure if the Mayor in 1857 & 1867 was the same one who complained of intimidation in 1882.

Acknowledgements:

Victoria History of Wiltshire, A History of Marlborough by J E Chandler.

Marlborough and the Upper Kennet Country by A R Stedman,

Waylen’s History of Marlborough and Nick Baxter.

The Marlborough History Society would like to send their thanks to The Merchants House, Marlborough for kindly giving permission to post this article on our website. The article was published in The Marlborough Journal, Issue 64.